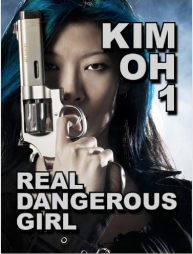

At Long Last! K.W. Jeter was kind enough to let us interview him for our website. One of the original Steampunk Trio, and the writer of the letter to Locus naming the genre, Mr. Jeter currently resides in Ecuador where he writes the Kim Oh series.

1. Let’s begin by getting a little background to set the stage a bit. Tell us a bit about your time at California State University.

I started at CSUF when it was still California State College at Fullerton; that would have been around 1969 or so. My family was living in Orange County at the time, so the state college in Fullerton was pretty much the easiest choice to make if you didn’t feel like leaving the area, or you didn’t have the financial resources to go somewhere else. It was a pretty blue-collar school then; I majored in sociology, and most of the classes were about social research methods, training students to be clipboard jockeys on research projects, rather than about big-idea theories. Frankly, I think that was a pretty useful education, because it tended to develop a tough-minded attitude about scientific and political matters – when the first thing you learn is that your job as a researcher is to go find the evidence to prove what the people writing the checks want to be proven, then you’re going to be pretty skeptical about everything you read in print or online.

At the same time, I picked up enough classes in the English department that I was close to having a double major in that. There were some real fine instructors there – Willis McNelly was teaching classes in science fiction, treating it as a subject worthy of literary consideration, and I believe he was one of the first professors in the US to do that. I never took any of his classes, but I had a lot of discussions with him, and he was responsible in a roundabout way for my meeting Philip K. Dick when he came to live in Orange County. Another great instructor in the English department was John Schwarz, who was quite a fine novelist himself; I took a class in short stories from him. Tim Powers might have been in that class as well, but I’m not sure at the moment; I do remember that Tim and I took a seminar in Faulkner’s Snopes trilogy from another instructor who was kind of crazy; fun, though.

You also have to remember that there was a war on at that time. I got pretty active in the anti-war stuff that was happening on campus, just as it was happening all across the country. I’m proud of everything I did in that regard, and only regret that I wasn’t able to do more. But there were some tense times on campus, building occupations, etc. At one point, when the police were all over the campus in their riot gear, I wound up having about a dozen shotguns pointed at my head, because I was the guy holding bullhorn. Stuff like that tends to make you think – but we did stop the war, so all good.

Other things I remember about that time – there still were some of the old orange groves left at the edge of the campus, from back when the site had been all agricultural and before the college had been built. They orange trees were completely neglected, but they did get the water run-off from the football fields. Some of us used to go out there and pick the oranges – you had to watch out for those big fuzzy tarantulas in the weeds – and they were so sweet. You can’t get oranges like that any more. I doubt if those trees are still there.

2. What drew you to Science Fiction?

It’s what I grew up reading. The public library in Norwalk, where I grew up, put a little rocket ship symbol on the spines of the sf books, and I would just go down the shelves, looking for the little rocket. I was so young that I didn’t even know at first that the books were written by different authors. At some point, though, I realized that some of the books were better than others – or at least I enjoyed them more – and that there were specific authors’ names attached to the good ones, and then I would look for more by those names. Andre Norton was my big favorite – I thought her juvenile sf novels were much better than, say, Robert Heinlein’s. Still think she’s a much underrated author in the field.

Plus you could buy cheap paperback sf novels back then, usually for thirty-five cents or so. The ones from the Ballantine Books publisher seemed the best to me; books like Ward Moore’s Greener Than You Think, Frederick Poul and C. M. Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants, Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human – they all had a big impact on me.

The other big influence was The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, when it was edited during those Sixties years by Avram Davidson. There was never a better sf magazine than Davidson’s F&SF; as far as I’m concerned, that was when the sf short form reached its peak.

3. The other authors who are credited with creating Steampunk–James Blaylock and Tim Powers–you were all friends here at school. How did you meet? How would you describe your relationship?

Not quite sure at this point; that was a long time ago. Pretty sure I met Tim in one of the English department classes I took. One of the English instructors was a charismatic woman named Dorothea de France, later Dorothea Kenny – I dedicated Morlock Night to her, though due to a production error the dedication didn’t appear in the first paperback edition. But she ran something she called the Poetry Club, where students would come and read their stuff aloud. I believe I met Jim there – he and Tim would go there just to cut up and have fun, and generally snicker at whatever drippy sensitive poems somebody had written. Which was why I was there, too. Tim and Jim were closer buddies than I was with them, probably because of my involvement with all the political and anti-war stuff, which they weren’t into as much.

4. What inspired Steampunk? How did it originate and grow from an idea to a reality?

Actually, I don’t think anything inspired steampunk as much as simply a desire to write some entertaining fiction, which drew upon a mutual interest in what ot her people looked down upon as stodgy old books, but which Tim and Jim and I admired – sometimes because that old stuff was really good, but also just because it was a way of separating ourselves from everybody else in the Engli

her people looked down upon as stodgy old books, but which Tim and Jim and I admired – sometimes because that old stuff was really good, but also just because it was a way of separating ourselves from everybody else in the Engli

sh department, who were all into god-awful stuff like Virginia Woolf. In that sense, there’s a certain reactionary element to the enthusiasm for those good old books and writers that nobody else is reading, which connects up with an enthusiasm for science fiction, which back then most people thought was just trash. “Oh, you think those writers are so great? Yeah, well, they ain’t squat; these dusty old novels and cheap sf paperbacks are the real shit.”

5. When you wrote the letter to Locus naming “steampunk” as a genre, what was your ultimate goal?

Didn’t have one; it was a joke. Because of the cyberpunk thing taking off right around that time – which I didn’t much care for – there was a whole spate of “something-punk” subgenres being bandied about. That’s what I was mildly satirizing, the whole bit of putting some modifier in front of the word “punk” and trying to convince people something important was going on because of it. Just goes to show that you have to be careful about the jokes you make – you never know what’ll happen with them down the line.

6. Fullerton and Cal State Fullerton both make appearances in books by the three of you. Do you believe that your location here–CSUF, Orange County, and Southern California–was an influence of Steampunk’s creation? If so, does this location play an integral part of the foundation behind Steampunk?

I’m not sure that Fullerton and Cal State Fullerton figure very prominently in any of my writing. Orange County does, especially in my first novel Dr. Adder, because as a location it’s a thematic and psychological foil to Los Angeles, which was always my true dream landscape. In that sense, there’s a dichotomy between the two landscapes – to use the language of the time, Orange County was Squaresville and L.A. was hipster territory. It was a big deal for me when I finally shook the dust of Orange County off my shoes and moved to L.A., which was where my real life began, so to speak. Sort of a translation of my writing into my autobiography. As for any effect upon steampunk, I’m not quite sure, except to the degree that setting stories in Victorian London kind of expressed a yearning for the old and what seems genuine, rather than the plastic and artificial that seemed to typify Orange County back then. Though, of course, I’m sure Orange County is much hipper now.

7. Steampunk has been described as a counterculture, hence the “punk” part of the name. How would you describe what exactly puts the “punk” in Steampunk?

At a certain point in my novel Fiendish Schemes, a character talks about the “punk” suffix as expressing an enthusiasm for things that other people just aren’t into, or not to the same excessive degree. In cultural matters, I guess that’s what “punk” denotes now. At the beginning, with maybe the whole Malcolm McLaren/Sex Pistols thing, it indicated an association with stuff that other people actively despised, and an aggressive rejection of stuff that other people cherished. You talk to survivors of the original King’s Road punk scene, and they’ll tell you that to be a punk back then meant that you had to be ready for and actually look forward to a violent physical confrontation at any moment. Whereas steampunk, as a counterculture, seems a lot more genteel than that now; I doubt if anybody’s getting beat up for wearing a top hat with goggles nowadays. So in that, as a language usage, “punk” indicates mostly a state of eccentric enthusiasm.

8. Much of punk literature looks into our potential future. You did something new with Steampunk by looking, instead, at our potential past. What was the appeal?

A lot of times, at the moment when you’re writing something, you don’t know what the appeal is. There’s a charm to old Victorian novels and the settings associated with them – that’s why tourists go to London with their guidebooks in their hands and look at moldy old buildings. Those things are just innately interesting. To the degree that steampunk has become a genre in which writers, myself included, can take a sort of deconstructive look at the past and critically imagine how else things might have been – well, that’s something that’s developed along the way, and a long time after the beginning of the whole thing.

9. You have since moved forward with the Kim Oh series of novels. Are these novels a complete departure from Steampunk? Do Steampunk and Kim Oh both find their roots in cyberpunk?

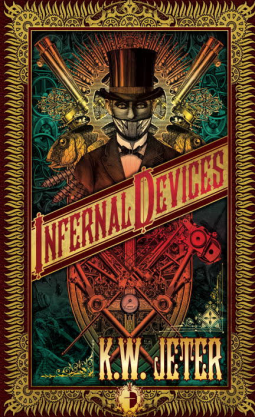

Pretty much a complete departure from steampunk, except to the degree  that the rapscallion semi-modern characters in Infernal Devices and Fiendish Schemes connect with the sort of living-by-her-wits character Kim Oh. By way of contrast, the Dower protagonist in my steampunk novels is rooted in his landscape, and is increasingly lost when the landscape starts to change underneath him – whereas Kim Oh is self-admittedly feral in nature, and is at home nowhere. So she can run faster, so to speak, and duck and weave in a way that Dower can’t. In a sense, Dower is frustrated, because he’s appalled at what the world is becoming, whereas Kim Oh has a certain sadness to her, because she’s never had the kind of home that Dower has lost.

that the rapscallion semi-modern characters in Infernal Devices and Fiendish Schemes connect with the sort of living-by-her-wits character Kim Oh. By way of contrast, the Dower protagonist in my steampunk novels is rooted in his landscape, and is increasingly lost when the landscape starts to change underneath him – whereas Kim Oh is self-admittedly feral in nature, and is at home nowhere. So she can run faster, so to speak, and duck and weave in a way that Dower can’t. In a sense, Dower is frustrated, because he’s appalled at what the world is becoming, whereas Kim Oh has a certain sadness to her, because she’s never had the kind of home that Dower has lost.

Nothing I’ve written has any roots in cyberpunk. Never even read any of the stuff.

10. How much has Steampunk shifted and grown away from your initial brainchild?

Hugely, but that’s evolution. That’s a good thing. It also reflects that a lot of younger, talented writers have come along and seen it as a way of writing that they could do something interesting with. They’ve taken it and made it their own, and more power to them, I say.

11. How would you react to someone who claimed Steampunk was all goggles and gears? That is to say, Steampunk has become more of an aesthetic than a genre (or sub genre)?

I would say, “Look, just read some of the books that’ve been written. See what’s been done.” If somebody judges the literary subgenre by the just-having-fun costuming culture with which it’s associated, then that would be a foolish judgment. It’d be like judging historical fiction by the people who dance around in pseudo-medieval costumes at a Renaissance Faire. So there’s a bifurcation here – there are a lot of really good books, and really good writing, on one side, and on the other side there are people who enjoy dressing up with clockwork gears stuck all over themselves. It’s not a tragedy that there’s only a slight overlap between those two different areas, and that the same word “steampunk” is applied to both. People need to relax and see each one for what it truly is.

You must be logged in to post a comment.